A Rider’s Guide To Crank Length

Author: Matt Appleman

Publish Date: January 8, 2023

Updated: November 25, 2024

Crank length is super weird.

For some riders, crank length is the key to a good fit—while others seem unfazed by it.

Shorter cranks may enable pain free riding for one rider—while it causes pain for another.

Crank length is confusing.

It’s an emotional and triggering subject for many, so this article will try to be gentle for those with tightly held beliefs while also enlightening those whom are interested in a fresh take.

Let’s take a look at the mystical and magical creature of crank length.

My Cranks Fit. Don’t They?

Maybe. Crank length has been largely ignored for decades by the bike industry. Everyone agrees that bikes should come in different sizes to match different sized riders. That’s a given. So why not crank length too?

Let’s look at some differences of common size ranges:

Frame sizes: 48cm to 62cm, a range of 25%

Stem sizes: 40mm to 140mm, a range of 111%

Handlebar width (road): 38cm to 46cm, a range of 19%

Rider height: 5’0” to 6’5” (1.52m to 1.96m), a range of 25%

Rider inseam: 26” to 36” (0.66m to 0.91m), a range of 32%

Crank lengths: 165mm to 175mm, a range of 6%

That’s bonkers. Why only a 6% range in crank length? Maybe it’s the manufacturing methods of the old days, cost savings, or an unwillingness to change. Probably a little bit of each.

The problem with the industry norm—165’s are for short people and 175’s are for tall people—is that the scale is all wrong.

We need to have a wider spread of crank lengths available and shift the average crank length.

165mm is a great length, but it shouldn’t be reserved for only the shortest of riders. 175’s are great too… if you’re on the tall end of the spectrum.

A better approach:

- 155mm and 165mm cranks for most riders (average)

- 145mm and 175mm crank for riders towards the ends of the spectrum

- 135mm and >175mm for a few outliers

While we’re at it, can we ditch the 2.5mm increments? 2.5mm increments in crank length should be banished from the crank length kingdom. A 2.5mm change, it’s something—a start—a pat on the back—a gold star, but definitely not worth swapping out new crankset for. As we’ll see later in this guide, 10mm changes make a significant impact on rider fit and comfort.

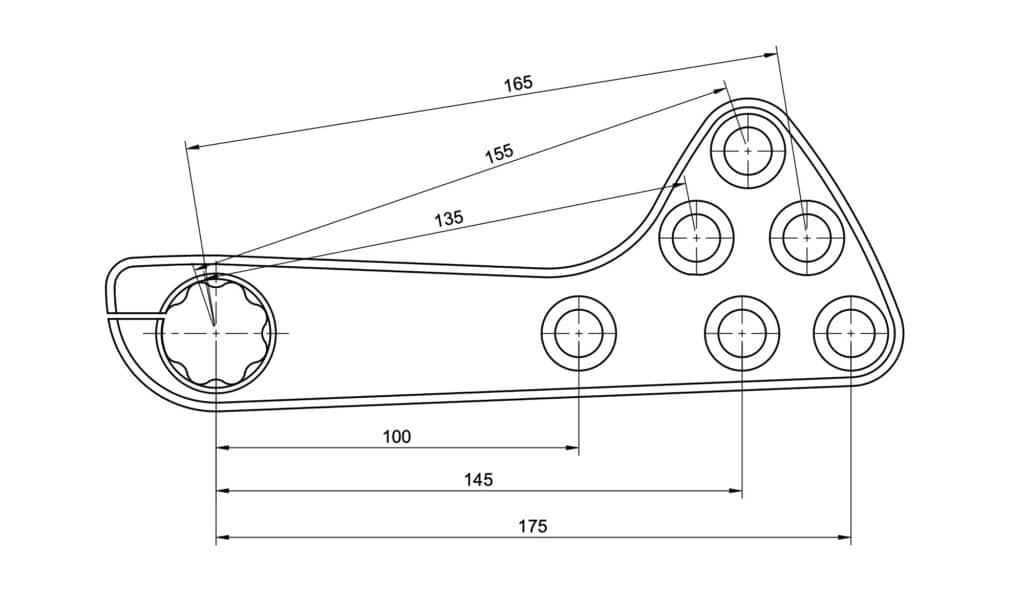

This is why the Appleman 2XR Crankset offers crank lengths in 135mm to 175mm a range of 26% to actually match the people who pedal.

Why Bother Changing Crank Length?

In a word: comfort.

In three words: comfort, stability, speed… or… better bike fit.

If you’re pain free and riding your best life… by all means… skip a crank length change. Save money and keep on keepin’ on.

Consider a change in fit and crank length if you:

- have pain (knee, hip, back) (PS: riding doesn’t need to hurt, even after a long ride)

- Your riding buddies say that you ride “all over the bike”

- rocking hips/torso

- your knee tracks outward at the top of the pedal stroke

- are of average or short height (some tall folks can benefit too)

- have a history of discomfort on the bike

- want more speed

- want a better fitting bike

- feel that something isn’t quite right with the world

Crank length works it’s magic at the top of the pedal stroke.

Shortening the crank will straighten out the leg—reducing knee and hip angles—enabling the benefits listed below.

Flex Less, Pain Less: Shorter cranks may reduce knee or hip pain. Excess bending of the knee or hip causes increase stress (possible pain or injury). With a shorter crank, the legs flex less at the top of the pedal stroke increasing comfort. The reduced range of motion of the hip also helps folks with hip impingement.

Easy Breathy Beautiful: Breath easier. At the top of the pedal stroke, a shorter crank moves the leg away from the belly and chest for more breathing room.

Easy Speedsy: Get more aero and more speed by adopting a lower position with the additional torso-to-leg clearance from shorter cranks.

If the hips are a Rockin’, don’t come a knockin’: Low back pain, saddle sores, and loss of power can be caused by the back and forth rocking of the hips. This is common when cranks are too long, the rider isn’t flexible enough or the saddle is too high.

Rocking occurs every pedal stroke when the rider subconsciously lifts their hip (like letting out a fart… excuse my graphic language) to get their leg over the top of the pedal stroke.

Shorter cranks can position the legs within a comfortable range of motion for the rider, increasing stability of the hips while riding.

Pedal Strike: Shorter cranks move the pedal away from the ground resulting in fewer pedal strikes. Life is better when your pedals aren’t smashing rocks or clipping the pavement.

Toe Overlap: Does your toe ever hit your front wheel? Then you’ve got toe overlap. Guess what, shorter cranks help reduce that as well.

How to Choose Crank Length

Ok, ok, I get it, crank length is important. Soooooo what is the best crank length for me?

That’s the bajillion dollar question!

Meaningful Impact

Keep in mind that a 10mm (or more) change in crank length will have a meaningful impact on your fit. Expect a tiny impact from a tiny change of 2.5mm in crank length. Don’t bother swapping cranks unless you’re making a >5mm change to crank length.

Knee & Hip Angles

The best way to predict crank length without actually trying different cranks is driven by knee and hip angles. When these joints are bent past certain a certain limit—excess stress from pedaling may cause pain, discomfort, or pelvic instability on the saddle.

Crank length should be determined by whichever angle (knee or hip) is most limiting to the rider.

Knee Angle

No methodology is perfect, but looking at the knee angle (how bent the knee is) at the top of the pedal stroke is the most robust way I’ve found to predict crank length.

Schultz’s article , explains that there is a strong relationship between chronic knee pain and how flexed the knee is at the top of the pedal stroke.

In my experience fitting customers with short cranks and knee pain, I concurrently and unknowingly reproduced the same results as Schultz and confirmed that knee angles were critical to determining crank length.

Schultz’s article outlines clear numerical guidance for knee angles as follows:

Knee Angles less than 66° are most likely to cause knee pain.

Knee Angles between 66° – 69° may cause knee pain.

Knee Angles greater than 69° are not likely to cause knee pain.

How does one measure knee angle? A goniometer (a fancy protractor) is the most common way. You can also use a bit of trigonometry if you’re into that.

The angle is measured between the upper leg (femur) and lower leg (tibia)—when the knee is the most flexed (usually just behind top-dead-center, when the crank arm is roughly inline with the seat tube).

Mind blown right? But wait a second… how does knee angle convert to crank length? Here’s a handy dandy calculator.

Rule of Thumb: A 10mm change in crank length results in ~3.5° change* in Knee Angle**

*Technically, a 10mm change in crank length results in a 3-4° change depending on rider size. Riders with very short legs would use the upper end of this range and riders with very long legs use the lower end of this range.

**The number in this guide differs from Schultz’s article (where this value is doubled). The 3-4° range provided in this guide was measured on real riders and confirmed by computer modeling.

Hip Angle

The angle of the hip between the upper leg and torso is also critical to comfort, speed, and performance. The measurement must be taken at the point hip angle is minimized (usually just in front of top-dead-center of the pedal stroke). See this in action: Figure 1 above.

Hip angle is difficult to measure.

Why? The hips interact with the flexible spine in addition to the legs and it’s this flexible spine that makes it difficult for the lay-person to measure the accurate orientation of the hips. Riders hunch and arch their backs to various degrees—rotating the hips—blurring the angle between the upper leg and hip-to-shoulder.

Numerically Speaking: Schultz’s article recommends a lower limit of 45°. You’ll commonly see 45°-55° in other fit literature. Guidance is not crisp and clear on ideal hip angles and measuring them is difficult so there is a lot of room for interpretation.

Gut Feeling: Sometimes we can’t rely on numbers, machines, and rules of thumb. Sometimes the best tool is our own bodies and sensing how they move.

The goal here is to minimize interference of the torso and the legs. If you’re bumping your chest or gut with your thighs every pedal stroke—change may be needed. If the leg is going too high (hip angle too small) at the top of the pedal stroke for your given upper body location, you can either shorten crank length or raise your torso.

The torso and thigh will always interact to some degree, but let me tell you, if feels good to get the belly off the legs. You don’t need a gut-massage every ride.

Professional Bike Fit

This is the most comprehensive option for determining crank length… and all other aspects of bike fit. Hopefully the fitter will have adjustable length cranks that you can try out during the fit.

That being said, bicycle fitters run the gamut of quality, experience, methods and knowledge—so do your research before paying up.

Look for a fitter who uses their eyes and observes you on/off the bike as their primary tool. Technology like lasers, tracking balls, etc… can be used primarily as an education tool for the rider, not the driver of fit results.

If you’re interested in how to find a bike fitter that is a good fit for you (pun intended), check out the Bicycle Fit Guru’s: Bike Fit Myths.

Try It or Buy It

Actually pedaling with a new crank length is an excellent way to decide if it’s right for you. You can always buy cranks and try them out, but if you’re the type who really wants to try it before you buy it—a session with a fitter with variable length cranks or variable length crank rental will be your ticket.

What if you could try different crank lengths—on your own bike—from the comfort of your own saddle?

Look no further than the Appleman 2XR FIT Crank Rental program.

Install one pair of cranks and try 6 different crank lengths from 135-175mm + a 100mm bonus crank length.

Crank Length Formulas

Formulas are the most basic way to determine crank length. While overly simplistic and not the most accurate, formulas are free and do a better job than current industry-standard recommendations.

Based on the must-read Crank Length VS Max Power study by Martin, James & Spirduso, W.

41% of Tibia Length

Measured from the center of the ankle bone to center of knee joint. Tibia length is more important than inseam length in regards to crank length. I’ve found this formula to provide more accurate results than inseam.

20% of Inseam

Measured crotch to floor while standing. The least accurate of the calculator estimates (but better than rider-height). A good place to start using a commonly known measurement.

Choosing a OPTIMUM Crank Length

A down-to-the-millimeter “optimum crank length” doesn’t exist. Rather, there are a range of lengths that’ll be beneficial to the rider.

There’s more often an upper limit of crank length than a lower limit. Going too long will cause pain, discomfort, or instability. Going too short will feel a little funny for a few minutes. You decide.

Anyone that can ride a 170mm crank, can also ride a 165mm (or less) just fine. Going longer is a higher risk.

When in doubt, round down.

How Does Riding Style Impact Crank Length?

Let’s look beyond physical size and look at how different types of riding may sway crank length.

The Gear Masher: Riders who are heavy on the pedals may get along well with shorter cranks. Thanks to physics, the force required for each pedal stroke goes up with a shorter crank. This allows gear mashers to mash even more effectively. A smaller range of motion may open up breathing and reduce belly massaging as well.

The Spinner: For riders who are light on the pedals and prefer a high cadence, a shorter crank naturally increases cadence about the same percentage as the change in crank length. (PS: you may want a smaller granny gear if you use it frequently).

Triathlon / Time Trialist: Get more aero and more speed with a lower handlebar position! Shorter cranks move your legs further away from the chest allowing you to get low get low get low.

Mountain Biker: Aside from the comfort short cranks offer… you’ll also be smashing pedals and crank arms into fewer rocks, roots and general rowdiness.

There’s the argument that longer cranks are better for mountain biking because of more leverage. The constant on-off accelerations while riding would lend itself to a leverage-happy crank. While longer cranks do offer more leverage, that same ease of acceleration can be accomplished with shorter cranks and an easier gear. It’s all a balance of comfort, clearance, gearing, and what aspect of riding you want to prioritize.

Weekend Warrior: Less pain, better fit, more fun. Shorter cranks can help make it happen.

The Pro: You want speed and to be injury free. Get more aero and reduce stress on the knees with shorter cranks.

What Else do I Need to Know?

Do I Need to Adjust My Bike After Changing Cranks?

Yes! when swapping crank lengths, saddle height is the most important change to make. For example, if switching to 20mm shorter cranks, you’ll want to raise your seat by ~20mm. By raising your saddle, you will maintain proper leg extension at the bottom of the pedal stroke.

Maintaining proper leg extension at the bottom of the pedal stroke is super important! Any adjustment to the saddle in any direction can change saddle height, so be ready to adjust, ride, and adjust.

Beware the Rabbit Hole: Everything is connected when it comes to bike fit and when making changes it’s very difficult to keep all of your #’s from a previous fit exactly the same (but it’s pretty easy to keep them close).

The amount of adjustment you want to make depends on how far the bike-fit-rabbit-hole you want to go.

Keep in mind, you might not want the same ol’ fit as crank length may open up new possibilities to your bike fit.

For most riders, a saddle height adjustment is all that is needed.

Optional—Saddle Fore-Aft Adjustment: You can move your saddle up AND back when shortening cranks. The exact amount of up/back depends, but again—you need to maintain the proper leg extension after the adjustment. Some trial and error will be necessary.

What about KOPS? The Knee Over Pedal Spindle (KOPS) measurement. Don’t worry about it, it’s a myth. Read more about seat setback and fore-aft balance on Steve Hogg’s site.

Optional—Handlebar Adjustments: Adjust handlebar height and reach to match the raise in saddle height/fore-aft.

How About Gearing?

You might want to change gearing if you change crank lengths, you might not. The human body is pretty incredible—it compensates and adapts to different terrain, pedaling rates and gears very well. A change in crank length may only change your cadence a few rpm here and there.

Physics dictates that a shorter crank requires more leg force for the same gear at the same speed. Since most bikes have gears, simply shifting gears will alleviate any misgivings.

In theory, the percentage change of crank length should equal the percentage change in your gearing.

In reality, many riders don’t need to change gears. If you’re already buying new chainrings try a 1/2 (one half) percentage change of crank length reduction in gearing.

It’s a matter of priority: all gearing has limitations so you want to make sure you’re setting your priorities. Are you climbing in your granny gear all day? Best add lower range. Are you in the peloton chilling at 30mph? You’ll want plenty of top end… or just spin faster.

How much smaller of a gear will I need? It depends on your riding style and how big of a crank length jump you’re making.

For example, going from 172.5 with a 40t chainring to 155mm cranks is a ~11% change. Finding a gear that is about half of that 11% would be a 38t, a 5% difference. Or say you’re currently riding a 32t chainring, then a 30t would provide a 6% reduction in gearing.

A note about fixed gear / singlespeed: When you only have one gear, the relationship between crank length, cadence, and gear choice becomes more important. I always recommend prioritizing joint health and comfort first. Leverage second (or third). Keep in mind that depending where/how you ride, the amount of time you need massive amounts of leverage is likely a small percentage of the whole ride.

Oval VS Round Chainrings?

Personal storytime: When I first started my knee-pain-crank-length exploratory journey… I was all about the oval chainrings. In fact, I rode oval chainrings for about 10 years as I figured out what crank lengths worked for me.

Oval chainrings reduced the stress on my knee at the top of the pedal stroke, woo woo! Doesn’t that sound familiar though?

With appropriately sized cranks… you don’t need oval chainrings.

So by the time I found 155mm or less cranks worked really well for me. I dreaded switching to a round ring. Lo and behold, once I tried a round ring, I didn’t hardly feel any difference because my legs didn’t need the help getting over the top of the pedal stroke. My body was much better positioned thanks to appropriate length cranks.

ATMO… oval chainrings and short cranks have many of the same goals, but short cranks and round chainrings do it better and more holistically than oval chainrings. The End

What about Power?

Research suggests that power is not strongly tied to crank length.

If it were, wouldn’t we all be riding 300mm long cranks?

No crank length discussion is complete without referencing the Martin, James & Spirduso, W study on max power of crank lengths between 120-220mm (Spoiler alert: 145mm topped the chart with 170mm coming in within just a few %).

I also power versus crank length testing by looking at average 1-minute power. See the Appleman Bicycles Case Study 01: Crank Length VS Power and Cadence for a bunch more info on this topic.

. . . and Leverage?

Everyone’s favorite argument against short cranks (understandably so): What about leverage?

I’ll say it again, if it were all about leverage, wouldn’t we all be riding 300mm long cranks?

Unfortunately, having a longer lever won’t make riders faster. Power makes us go faster and that’s based on the combination of crank length, force at the pedal and cadence.

If you spin a little faster on a shorter crank to make up for the loss of leverage, it all evens out. This is exactly why we have gears on bikes. Less leverage? Shift down a gear—physics just evened out the playing field.

More leverage feels really good when for when you need to lay down explosive power, like starting from a stop sign or standing up while on a super steep climb. While these are important parts of a ride, you should analyse the time you’re in these high-torque situations versus the amount of time you are riding with submaximal torque.

If you only have one gear, there is a more valid argument for more leverage. There’s always a balance of gear ratio versus terrain and use. Many riders report having a wider range of useful cadence when using shorter cranks and an easier gear.

What Does Changing Crank Lengths Feel Like?

When you first start pedaling a different length crank, it’ll feel a little odd. Don’t worry, the novel feeling quickly fades and the benefits will stick around.

One surprising thing—crank length is more noticeable while out of the saddle and that feeling takes longer to get used to.

Going Longer

Expect some instability/unwieldiness as your legs are moving in a larger range of motion.

A longer crank feels good while standing on the pedals and exerting very high force. This added leverage feels nice, but is limited by the amount of time you’re able to sustain the high power efforts.

Additional stress may be placed on the knees as they’ll be more bent at the top of the pedal stroke. Same goes for the hips.

Longer cranks will amplify the gut-massage-effect. While pedaling, the legs will gently churn/massage the lower gut. While this shifting of innards is not necessarily a bad feeling, it’s not great and feels much better when it’s minimized.

Note: longer cranks have less pedal-to-ground clearance so be mindful not to hit the pedal while cornering.

Going Shorter

Expect smaller circles, duh. The smaller range of motion won’t recruit any new musculature so you’ll adapt quickly.

You may notice a more open torso, less interference of the legs while breathing and less gut-massage-effect.

I recommend riding shorter cranks for at least a handful of rides to get used to them a bit.

Oddly, many riders notice the advantages of short cranks right away, but after switching back to long cranks they’ll really feel that the cranks feel loooong.

Conclusion

Congratulations for reading this far! It’s a lot of info to digest.

Crank length is confusing—and amazing—and important—hopefully you’ve found some clarity.

Current cranks have a small range of length offerings and don’t match up with the wide range of riders out there. 155mm and 165mm cranks are proposed to be the “new average” crank length sizes.

There are many benefits to decreasing crank length and fewer benefits to increasing crank length.

A crank length change of 2.5mm is not worth making. 10mm changes in crank length have real, impactful changes on fit.

Crank length can be determined many ways. Crank length decisions are best driven by knee/hip angles, riding style, and a little trial and error.

This page will evolve as we continue to learn about crank length. If you have any feedback, hate-mail, or suggestions, I’d love to hear it. Contact me here

-Matt Appleman, framebuilder and owner of Appleman Bicycles

About the Author

My crank journey begins with a knee injury. I grew up racing (road and track) happy as could be riding 172.5mm cranks. While in college I had chronic knee pain (patella tendonitis). Walking, sitting, riding… knee pain all the time.

To relieve the knee pain, I figured out that I needed custom geometry (a very slack seat tube angle to relieve pressure off my knees and better recruit my back end). I started building custom frames while I was a composite engineer. With a better balance on the bike, knee pain was manageable as long as I didn’t ride too long or too hard. This was all with 172.5mm cranks.

Happy to be riding, but not happy to be limited by distance and intensity, I started riding shorter cranks and building bikes around crank length.

165mm cranks helped a little bit, nudging up the distance and intensity I could ride. I thought why not keep going?

155mm cranks were a real game changer for me. My knee pain went away, as did any limit on distance and intensity on my rides. Woo wooo!

I started riding 155’s around 2014 and trying to understand the relationship between crank length and knee pain. Knee angle as well as fore-aft balance! Viola!

I started incorporating appropriately sized cranks for customers on the custom frame side of the business and they were hooked.

Fast forward to 2021, I started designing, prototyping and testing the 2XR Crankset. I was content with 155’s for many years, but holy smokes, the 145’s surprised me!

While the 155’s sufficiently opened up my knee angle, 145’s opened up my hip angle to a new degree that just felt so good—so comfortable.

So here I am, this 6’2″ tall guy riding 145mm cranks, happy as could be and leapfrogging my Strava PR’s. Thanks for reading and don’t be afraid to make change and get weird on the bike.